HURLING - CAMOGIE

Hurling - Iománaíocht - Iomáint is an outdoor team game of ancient Gaelic origin, administered by the Gaelic Athletic Association. The game has prehistoric origins, has been played for over 2,000 years, and is arguably the fastest field sport in the world and quite possibly the oldest. One of Ireland's native Gaelic games.

Camogie - Camógaíocht - Camoguidheacht is an Irish stick-and-ball team sport played by women; it is almost identical to the game of hurling played by men. Camogie is played by more than 100,000 women in Ireland and worldwide, largely among Irish communities. It is organised by the Dublin-based Camogie Association and also An Cumann Camógaíochta.

Hurling is played in most Irish counties, though the strongest teams tend to come from Kilkenny, Tipperary, Wexford, Cork, Clare, Offaly, Limerick and Galway.

Every year the counties compete over the Summer months in the All Ireland Championship , the winner of which receives the Liam McCarthy Cup / The MacCarthy Perpetual Challenge Cup. Matches in the Championship series attract huge crowds, with over 70,000 typically attending the final each September in Croke Park in Dublin.

Hurling is also played throughout the world, and is popular among members of the Irish diaspora in North America, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and Argentina.

There is no professional league, so the players today are unpaid amateurs.

The object of the game is for players to use a wooden stick called a hurley (in Irish a camán) to hit a small ball called a sliotar between the opponents' goalposts either over the crossbar for one point, or under the crossbar into a net guarded by a goalkeeper for one goal, which is counted as three points. Points can only be scored by striking the sliotar with the hurley, handpassed scores do not count. A goal is signalled by raising a green flag, placed to the left of the goal. A point is signalled by raising a white flag, placed to the right of the goal.

An impressive hurling skill is the ability to bounce or balance the ball on the hurley while running at full speed before finally flipping it high into the air and whacking it over or under the cross bar.

A player who wants to carry the ball for more than four steps has to bounce or balance the sliotar on the end of the stick and the ball can only be handled twice while in his possession.

Baiting is allowed although body-checking or shoulder-charging is illegal. No protective padding is worn by players. A plastic protective helmet with faceguard is mandatory for all age groups, including senior level, as of 2010. Players names are absent from their jerseys and a player's number is decided by their position on the field.

Hurling is played on a pitch approximately 137 meters long and 82 meters wide. The goalposts are the same shape as on a rugby pitch, with the crossbar lower and wider than in rugby, slightly higher and narrower than in soccer.

The playing stick is called a Hurley - Camán (pronounced “kay-maan”) It measures between 70 and 100 cm (28 to 40 inches) long with a flattened, curved blade end (called the bas) which provides the striking surface. At the same end the "heel" of the hurley is the area to the left of the band and at the hurley's edge. It is used to give height to a ball struck on the ground. Steel bands are used to reinforce the flattened end of the hurley though these are not permitted in camogie due to increased risk of injury. Bands have been put on hurleys since the beginning; the 8th century Brehon Laws permit only a king's son to have a bronze band, while all others must use a copper band. The rounded area to the right of the band is the "toe" of the hurley and is implicated in the roll lift or jab lift techniques which allow a player to gain legal possession of a ball into the hand from the ground. The handle is at the opposite end of the hurley to the bas, with the timber cut to form a small lip at the peak for a solid grip. A hurley is also used in camogie.

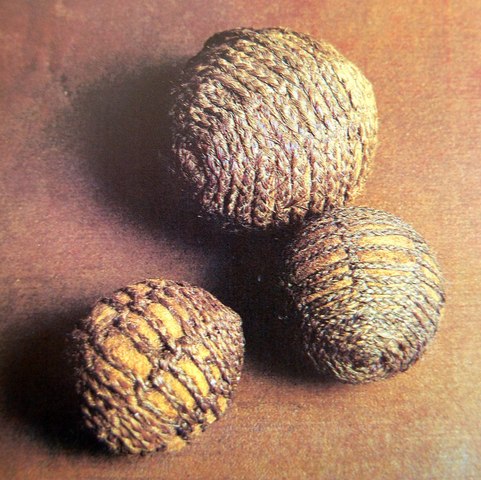

The playing ball is called a Sliotar - Sliothar (pronounced “slit-er”) and is a hard solid sphere slightly larger than a tennis ball, consisting of a cork core covered by two pieces of leather stitched together. It measures 69 mm and 72 mm in diameter, weighs 110g to 120g, the rib height is between 2 mm and 2.8 mm, and width between 3.6 mm and 5.4 mm and the leather cover can be between 1.8 mm and 2.7 mm and is laminated with a coating of no more than 0.15 mm. Approved sliotars carry a GAA mark of approval.

The playing ball is called a Sliotar - Sliothar (pronounced “slit-er”) and is a hard solid sphere slightly larger than a tennis ball, consisting of a cork core covered by two pieces of leather stitched together. It measures 69 mm and 72 mm in diameter, weighs 110g to 120g, the rib height is between 2 mm and 2.8 mm, and width between 3.6 mm and 5.4 mm and the leather cover can be between 1.8 mm and 2.7 mm and is laminated with a coating of no more than 0.15 mm. Approved sliotars carry a GAA mark of approval.

Each team consists of 15 players who wear a jersey with their team colors and logo. Two competing teams must have different color jerseys. The goalkeepers jersey must be different to the jersey of any other players.

Teams are allowed a maximum of 5 substitutes in a game, not including blood subs. Players may switch positions on the field of play at any time.

The game is played over 2 halves of 30 minutes for club level or 35 minutes at inter-county level.

When first seeing a hurling match, the impression is of great speed and on closer observation of remarkable skill and dexterity – it is truly not easy to catch and control a small hard ball travelling at up to 150km/hr (about 90 mph)!

Play moves rapidly up and down the pitch since it is possible for a good player to send the ball over 80 metres (about 260 feet) with a single strike. Scoring tends to be frequent, especially of points.

Cornish Hurling - Hurling the Silver Ball is an outdoor team game of Celtic origin played only in Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is played with a small silver ball. Not to be confused with Iománaíocht or Iomáint the Irish game of Gaelic origin which in the English language is also known as Hurling. There are profound differences between the two sports. Cornish Hurling is a ball throwing carrying game akin to Rugby Football. Irish Hurling is more a forerunner of modern Hockey played with a Hurley stick that is used to propel a ball called a Sliotar.

The Hurlers - A Group of 3 Stone Circles derives from a legend, in which men were playing Cornish hurling on a Sunday and were magically transformed into stones as a punishment. The earliest mention of the Hurlers was by historian John Norden, who visited them around 1584. They were also described by William Camden in his Britannia of 1586. In 1754 William Borlase published the first detailed description of the site.

HISTORY

Hurling is older than the recorded history of Ireland, and is thought to predate Christianity. Hurling is believed to be the world’s oldest field game. When the Celts came to Ireland as the last ice age was receding, they brought with them a unique culture, their own language, music, script and unique pastimes. One of these pastimes was a game now called hurling. It features in Irish folklore to illustrate the deeds of heroic mystical figures and it is chronicled as a distinct Irish pastime for at least 2,000 years.

There are actually two hurling traditions on the island of Ireland. In the north of the country a winter game, very similar to modern Scottish shinty, was played mainly on the ground with a narrow stick and a hard ball. The second form of the game, or Leinster hurling, was played with a broader hurley and a softer ball and was much more like the modern game. Players could pick up the ball, catch and strike it as well as soloing down the field. Although the GAA used both forms as an inspiration for the game it organised in the late nineteenth century, Leinster hurling had more of an influence in the evolution of the game. However, which of these games is the oldest remains a mystery.

The hurling rules were few and the number of players varied from 20 upwards however the custom was to adjourn to the ale house afterwards for drinking, singing and dancing.

The number of players was specified in 1885 as being 21, it was reduced to 17 in 1892 and to 15 in 1913.

Up to 1892 a goal had no equivalent so no number of points could equal a goal, the team scoring the greater number of goals won. In 1892 a goal was equal to 5 points and in 1896 to 3 points.

In historical texts records show evidence that hurling was a regular pastime in Ireland for well over 2,000 years. In fact the 1st recorded reference to hurling dates to the Battle of Moytura, near Cong in County Mayo (West of Ireland) in 1272 BC between the native Fir Bolg and the invading Tuatha De Danann. When both sides were preparing for battle they decided to have a hurling contest between 27 of the best players from each side. Both sides fought a bloody match and in the end when they were bruised and broken, the Fir Bolg would be victorious. The Tuatha Dé Danann then contest the ownership of Ireland with the Fir Bolg and their allies in the First Battle of Moytura (or Mag Tuired). The Tuatha Dé Danann are victorious and drive the Fir Bolg into exile among the neighbouring islands. But During the battle, Sreng, the champion of the Fir Bolg, challenged Nuada to single combat. With one sweep of his sword, Sreng cuts off Nuada's right Arm. Nuada, the king of the Tuatha Dé Danann is forced to renounce his crown. For seven unhappy years the kingship is held by the half-Fomorian Bres before Nuada's physician Dian Cécht fashions for him a silver arm, and he is restored. War with the Fomorians breaks out and a decisive battle is fought: the Second Battle of Moytura. Nuada falls to Balor of the Evil Eye, but Balor's grandson, Lugh of the Long Arm, kills him and becomes king. The Tuatha Dé Danann enjoy one hundred and fifty years of unbroken rule.

The earliest written references to the sport are in the Brehon laws which date from the fifth century.

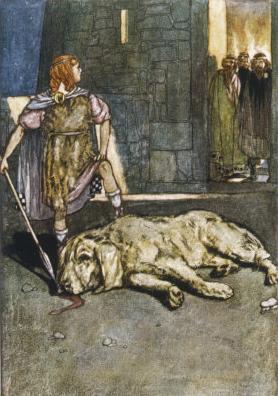

The tale of the Táin Bó Cuailgne describes the Ulster hero Cúchulainn playing hurling at Emain Macha. Hurling is mentioned a number of times in the text, most notably when the young hero, then known as Setanta, uses a hurley and sliotar to kill the vicious hound of Ulster.

Many Irish legends mention hurling, but none mention its roots. The sport has a major role in the legend of Cuchulainn, who was a Herculean type of hero. The legends, which were revived from extinction by Sechan Torpeist, a 7th century bard, tells the story of how Setanta, the nephew of King Conchobair Mac Neasa of Ulster, receives the name of Cuchulainn:

Setanta journeys to his uncle's court to join the boy's corps. He shortened his walk by hurling his silver sliotar (ball) and then throwing his bronze hurley stick after it. He would run and catch both the sliotar and the hurley stick before they hit the ground. Soon he arrived at court, and his hurling abilities amazed the boys of the corps. Legend has it that he was able to score with ease and when he guarded the goal he never let a shot in.

One day King Conchobair was invited to a banquet at the house of Culainn and asked his nephew to join him. Setanta agreed to go after he finished playing a hurling game. While at the feast Culainn asked the king if all the guests had arrived. King Conchobair, forgetting about Setanta, said yes and Culainn unleashed his hound to guard the house.

When Setanta arrived at the feast the great hound leapt up to attack him, but Setanta quickly hurled the sliotar at the hound and it went down the beast's throat. The boy immediately grabbed the stunned hound by his feet and smashed its head into the floor of the stone courtyard killing him.

When the guests heard the baying of the hound they ran outside and were surprised to see Setanta alive and the beast dead. King Conchobair was overjoyed but Culainn was sad at the loss of his favorite hound. Setanta offered to find a hound worthy of the one he had slain and vowed to guard Culainn's home until such an animal could be found. Thus Setanta became known as Cuchulainn, which translates to "the hound of Culainn".

Although the surviving version of this epic dates from the 12th century it has been convincingly argued that the story’s origins lie in the Iron Age (500 BC – 400 AD).

Similar tales are told about Fionn Mac Cumhail and the Fianna, his legendary warrior band.

Meallbreatha describes punishments for injuring a player in several games, most of which resemble hurling.

The Seanchás Mór commentaries on the Brehon Law state that the son of a rí (local king) could have his hurley hooped in bronze, while others could only use copper. It was illegal to confiscate a hurley.

Hurling continues to feature in Later Medieval Gaelic Irish and English sources, with the latter generally disapproving. It is hard to believe it now but in the 14th century that bastion of the modern game, Killkenny, attempted to ban hurling. This occurred in 1366 when the infamous Statutes of Kilkenny declared ‘do not, henceforth, use the plays which men call horlings, with great sticks and a ball upon the ground, from which great evils and maims have arisen’. Despite threats of fines and imprisonment, this law failed miserably and the black-and-amber-clad men of Kilkenny would become one of hurling’s powerhouses.

Similar measures to curtail hurling were also undertaken in Galway. These statutes, which were enacted in 1527, stated that people should ’At no time to use ne occupy ye hurling of ye litill balle with the hookie sticks or staves.’

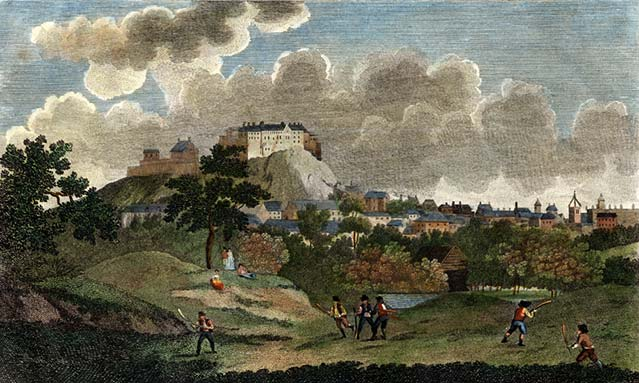

The Eighteenth Century is frequently referred to as "The Golden Age of Hurling". This was when members of the Anglo-Irish landed gentry kept teams of players on their estates and challenged each other's teams to matches for the amusement of their tenants.

Hurling has been played by Royalty and Political Leaders throughout time. This artwork by John Hogarty, circa 1831 shows hurlers at Derrynane, Co. Kerry, home of Daniel O'Connell, who can be seen on the left of the picture.

O'Connell was an Irish political leader in the first half of the 19th century.

"Wellington is the King of England", King George IV once complained, "O'Connell is King of Ireland, and I am only the dean of Windsor." The regal jest expressed the general admiration for O'Connell at the height of his career.

One of the first modern attempts to standardise the game with a formal, written set of rules came with the foundation of the Irish Hurling Union at Trinity College Dublin in 1879. It aimed "to draw up a code of rules for all clubs in the union and to foster that manly and noble game of hurling in this, its native country".

He was greatly interested in Gaelic culture, language and literature. An athlete in his youth, he was also interested in Irish games. He organised athletics in Dublin where he worked as a civil servant. Cusack believed that Irish games were in danger of dying out. Athletics in particular, witnessed a decline in participants. Athletes were then under the control of the English Amateur Athletics Association.

In the early 1880’s Cusack turned his attentions to indigenous Irish sports. In 1882 he attended the first meeting of the Dublin Hurling Club, formed ‘for the purpose of taking steps to re-establish the national game of hurling’.

The weekly games of hurling, in the Phoenix Park, became so popular that, in 1883, Cusack had sufficient numbers to found ‘Cusack’s Academy Hurling Club’ which, in turn, led to the establishment of the Metropolitan Hurling Club.

On Easter Monday 1884 the Metropolitans played Killiomor, in Galway. The game had to be stopped on numerous occasions as the two teams were playing to different rules.

It was this clash of styles that convinced Cusack that not only did the rules of the games need to be standardised but that a body must be established to govern Irish sports.

Cusack was also a journalist and he used the nationalist press of the day to further his cause for the creation of a body to organise and govern athletics in Ireland.

Cusack now considered founding a national organisation to preserve Irish games, and published anonymous articles about this in nationalist newspapers. On 11 October 1884, in the papers of the United Ireland and the Irish Sportsman published his article ‘A Word About Irish Athletics’. Here Cusack appealed to the Irish people to reject English sports and customs, which he described as ‘imported and enforced’. He believed they would destroy Irish nationality. He condemned the holding of athletic meetings in Ireland under the rules of England’s Athletic Association. These rules did not allow competitors to take part in sporting events held by other organisations. He thought Irish people were abandoning their sports and activities, played in the open, in fields and at cross-roads. He thought they were demoralised by the terrible Famine of 1846-52, by poverty, and by English laws, and they had gone ‘back to their cabins’. Cusack urged them to come out and play distinctively Irish games. He felt they would improve their physical condition and morale. This would also discourage anglicisation, give people an interest in Irish culture and traditions, and stimulate pride in place and nation.

Within days, Maurice Davin wrote to the papers supporting Cusack’s ideas and he declared he was willing to help establish and run a new sporting organisation. Davin, a farmer near Carrick-on-Suir, had been a talented and successful international athlete. His ideas about sport and his reputation as a moderate nationalist won him great respect in the countryside and among the urban Catholic middle class.

A week later Cusack and Davin submitted a signed letter to both papers announcing that that a meeting would take place on 1 November 1884 in the billiards room of Hayes's Commercial Hotel, Thurles, in County Tipperary.

On this historic date Cusack convened the first meeting of the Cumann Lúthchleas Gael, or the Gaelic Athletic Association for the purpose of forming an association for the preservation and cultivation of national pastimes.

It was an inauspicious beginning for such a remarkable organisation. The minutes of the meeting record the names of just seven attendees – although another six men sometimes claimed to have been present. The seven who did turn up were: Michael Cusack, Maurice Davin, John Wyse-Power, John McKay, JK Bracken, Joseph O'Ryan and Thomas St George McCarthy.

The founders were a mixed bunch. Davin, a Carrick-on-Suir man, was probably the best-known of them as he was one of the leading athletes of the day. Wyse-Power was editor of the Leinster Leader and a member of the IRB.

McCarthy, on the other hand, was a Tipperary man who was a District Inspector in the Royal Irish Constabulary, the police force of the British authorities in Ireland. Bracken was a building contractor from Templemore, O'Ryan was a solicitor from Carrick-on-Suir and McKay was a journalist from Belfast who was working for the Cork Examiner.

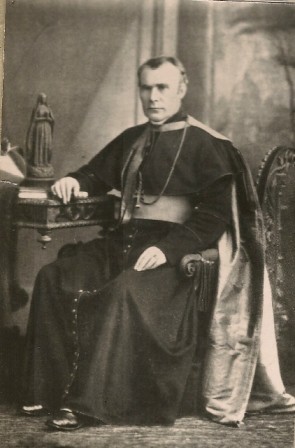

The new body elected to invite appropriate persons to be patrons of the organisation. They approached Dr Thomas Croke, the Archbishop of Cashel, Michael Davitt, head of the Land League and Charles Stewart Parnell leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party. While Parnell and Davitt had little to do with the rise of the GAA, the energetic and inspiring Dr Croke proved an excellent choice. His letter of acceptance to the Board was regarded as an unofficial charter for the GAA. Its fiery nationalist rhetoric gives some idea of the heady atmosphere in which the GAA was conceived.

‘We are daily importing from England, not only her manufactured goods, which we cannot help doing, since she has practically strangled our own manufacturing appliances, but, together with her fashions, her accents, her vicious literature, her music, her dances and her manifold mannerisms, her games also and her pastimes, to the utter discredit of our own grand national sports and to the sore humiliation, as I believe, of every genuine son and daughter of our old land. Ball-playing, hurling, football-kicking, according to

‘We are daily importing from England, not only her manufactured goods, which we cannot help doing, since she has practically strangled our own manufacturing appliances, but, together with her fashions, her accents, her vicious literature, her music, her dances and her manifold mannerisms, her games also and her pastimes, to the utter discredit of our own grand national sports and to the sore humiliation, as I believe, of every genuine son and daughter of our old land. Ball-playing, hurling, football-kicking, according to

Irish rules, casting, leaping in various ways, wrestling, handy-grips, top-pegging, leap-frog, rounders, tip-inthe-hat and all the favourite exercises and amusements among men and boys may now be said to be not only dead and buried but in several localities to be entirely forgotten and unknown ... Indeed, if we keep travelling for the next score years in the same direction that we have been going in for some time past, condemning the sports that were practised by our forefathers, effacing our national features as though we were ashamed of them and putting on, with England's stuffs and

broadcloths, her masher habits and such other effeminate follies that she may recommend, we had better, at once and publicly abjure our nationality, clap hands for joy at the sight of the Union Jack and place ‘England's bloody red' exultantly above the green.'

A second meeting was held in the Victoria Hotel, Cork, on 27 December 1884. It passed a resolution that the governing body of the GAA was to consist of the officers already elected, the committee of the National League, and two representatives from every athletic club in the country. The nationalist MP, William O’Brien, offered the GAA space in his newspaper, United Ireland, for weekly articles and notices.

At another important meeting, held at Hayes’s Hotel, Thurles, on 17 January 1885, rules were drawn up to regulate sports. It was decided to form a club in every parish in the country, and to ban members of any other sporting organisation from joining the GAA. The Dublin Harrier Clubs objected and organised opposition. They invited athletic and cycling clubs from all over the country to a meeting to oppose the ban. They declared that they ‘would not be bossed, ignored, put aside, or dictated to by any organisation’. E. J. Macredy, of Trinity College Dublin, proposed that athletes throughout Ireland should unite to ‘quash the Gaelic Union’, as he called the GAA. He argued that it was more political than sporting, and it wanted to promote only hurling. Cusack denied all this in the United Ireland. He argued that the GAA was not political and he condemned ‘the pernicious influence of those who encourage nothing but what is foreign to the Irish people and at which they can be easily beaten’.

The GAA held its first official social function at the end of January 1885 in the Ancient Concert Rooms, Dublin, to commemorate the Scottish poet, Robert Burns. This sporting and literary festival was intended to bring Irish and Scottish ‘Celts’ together, and promote Celtic sports and culture in their countries.

The GAA rules for hurling, football, athletics and weight-throwing were published in United Ireland in February 1885. The Irish Sportsman, in reply, published the rules of the Irish Amateur Athletic Union (IAAU), the older sporting organisation under the control of a British body. Davin publicly criticised the British association’s attempt to impose its rules in Ireland, and defended the GAA’s decision. Davin’s letter to the papers sparked more controversy. Mr Christian, spokesman for the IAAU, accused the GAA of ‘putting through rules purporting to govern all athletic sports’. Cusack responded angrily. Davin now intervened and encouraged a sense of good will between all athletes. Cusack and other prominent leaders in the GAA attended the next meeting of the IAAU in early February 1885. There was a very heated debate between the rival organisations. The IAAU criticised the GAA for holding games on Sundays and violating the Lord’s Day. Cusack retorted that rich people played games on the Sabbath and condemned poor people for doing the same.

Far from damaging the GAA, the controversy gained the organisation sympathy and support because of its emphasis on national games and the need to bring Irish athletics and other sports under national control. The number of affiliated athletic clubs grew rapidly, and athletics was the main concern of the GAA in its first year. New clubs sprang up, all over the country and abroad, to promote hurling and football. The games were to become extremely popular very quickly, and enjoy a widespread revival.

The GAA held its first Annual General Meeting (AGM) on 31 October 1885 in Hayes’s Hotel, Thurles. In the main address, Davin described the Association’s achievements in its first year. Most notably, 150 sporting meetings were held throughout the country—athletics, hurling and football—all of which got great public support. The chairman read a letter from Michael Davitt appealing to them to establish a pan-Celtic festival, a subject he returned to frequently. The most important item for discussion was the ban on GAA athletes from playing other games. The day before the AGM, theFreeman’s Journal published an article asking for reconciliation between the GAA and the IAAU, and urging both to abolish their exclusion rules and allow athletes to compete at all the meetings of both organisations. Croke appealed strongly for an end to the ban in a letter published in the Freeman’s Journal two days later. John Purcell, (an IAAU athlete), in the same paper, appealed for an amicable settlement for the good of Irish athletics. Cusack said that Archbishop Croke’s request would be submitted to the Executive Committee of the GAA, and, in the meantime, the ban would be removed:

‘The G.A.A. prizes are now open to all. We shall see where the best athletes are. Our movement is a national one. He who is not a nationalist—I use the word advisedly—no matter what his religion or politics may be, need not come near us except for a prize. Our prizes are open to all honest men.’

The Association also showed that it was in tune with the tenor of the times by undergoing a rancorous split early in its existence. Less than two years after the Thurles meeting, Cusack fell out with Croke and also incurred the wrath of the GAA in Cork. Wyse-Power engineered the removal of Cusack as Secretary, and the man who had started it all found himself out in the cold. Like Parnell after him in the political sphere, he found it impossible to regain his influence in the organisation he had pioneered. Two years later, Davin resigned as

President after another dispute and Wyse-Power quit shortly after that.

Despite the internal conflict, the GAA quickly gained a reputation for being well run and it wasn't long before it could lay claim to being the leading sporting organisation in the country. The attractiveness of the games of hurling and football and the opportunity they gave for the expression of local

pride were huge factors in this, but the efficiency of the Association had a lot to do with it too. It spread the revived games all over the country and by 1887 – just three years after its inception – was able to organise the first ever All-Ireland Football and Hurling Championships.

Under the new organisation the first county hurling championship was played in 1887 and Garranboy (near Killaloe) defeated Ogonnolloe in the final. The following year Ogonnolloe won the championship by beating Tulla in the final but all attention was focused on the Carrahan Tournament which commenced in September. The coveted prize was a banner 5ft. x 4ft. depicting a hurler with a caman and sliotar in a rural background.

This is known as the Carrahan Flag and is one of the oldest known G.A.A. Trophies. Two teams from Quin and two teams from Clooney participated in the tournament. It could not be completed that year and it was due to recommence in February '89, but due to the shooting of a local landlord, Arthur Creagh, it was further postponed until May. On Sunday May 18th, 1889 the final was scheduled for Carrahan between Tulla and Feakle with the flag being displayed during the match as an added incentive. Tulla's team were "remarkably active" and proved too good for the "strength and swiftness" of the Feakle teams winning by 2-3 to 1-2.

1913 Purchase of Croke Park

At the G.A.A.’s 1905 Annual Convention the decision was taken to erect a memorial in honour of Archbishop Thomas William Croke, First Patron of the GAA, who died in 1902. Between 1905 and 1913 fund-raising for this memorial was sporadic at best but in 1913 a ‘Croke Memorial Tournament’ (Hurling and Football) was held which resulted in a profit of £1,872, to be used for the memorial. Using these funds the GAA decided to purchase Jones Road Sports Ground from Frank Dineen for £3,500. They re-named the grounds ‘Croke Park’ in honour of Archbishop Croke.

1918 Gaelic Sunday

In 1918 the British Authorities informed Luke O’Toole that no hurling or football games would be allowed unless a permit was obtained from Dublin Castle. The GAA, at their meeting of July 20 1918, unanimously agreed that no such permit be applied for under any conditions and that any person applying for a permit, or any player playing in a match in which a permit had been obtained, would be automatically suspended from the Association. In a further act of defiance the Council organised a series of matches throughout the country for Sunday August 4 1918. Matches were openly played throughout the country with an estimated 54,000 members taking part. This became known as Gaelic Sunday.

PLEASE CLICK HERE to read the statement in full

Camogie - Camógaíocht - Camoguidheacht

The name was invented by Tadhg Ua Donnchadha (Tórna) at meetings in 1903 in advance of the first matches in 1904. Men play using a curved stick called in Irish a camán. Women would use a shorter stick, at one stage described by the diminutive form camóg. The suffix -aíocht (originally “uidheacht”) was added to both words to give names for the sports:camánaíocht (which became iománaíocht) and camógaíocht. When the Gaelic Athletic Association was founded in 1884 the English-origin name "hurling" was given to the men's game. When an organisation for women was set up in 1904, it was decided to Anglicise the Irish name camógaíocht to camogie

The 1st official game of Camogie took place at the Gaelic League Fair, with a public match between Keatings and Cúchulainns on July 17, 1903 in Dublin, Ireland. Different rules were drawn up earlier in 1903 for a female stick-and-ball game by Máire Ní Chinnéide, Seán Ó Ceallaigh, Tadhg Ó Donnchadha and Séamus Ó Braonáin.

Under Séamus Ó Braonáin’s original 1903 camogie rules, both the match and the field were shorter than their hurling equivalents. Matches were 40 minutes, increased to 50 minutes in 1934, and playing fields 125-130 yards (114-119m) long and 65-70 yards (59-64m) wide. Until 1979 a points bar was also used, meaning that a point would not be allowed if it travelled over this bar, a somewhat contentious rule through the 75 years it was in use. Teams were regulated at 12 a side, using an eliptical formation (1-3-3-3-1) although it was more a "squeezed lemon" formation with the three midfield players grouped more closely together than their counterpart on the half back and half-forward lines. In 1999 camogie moved to the GAA field-size and 15-a-side, adopting the standard GAA butterfly formation (3-3-2-3-3).

The Camogie Association was founded at; 8 North Frederick St, Dublin, Ireland on February 25, 1905, with Máire Ní Chinnéide as President. In 1911, it was reconstituted as Cualacht Luithchleas na mBan Gaedheal at a meeting organised by Seaghán Ua Dúbhtaigh at 25 Rutland Square (now Parnell Square), Dublin. It was revived in 1923 and the first congress held on the 25th April 1925, when over 100 delegates gathered in Conarchy's Hotel, Parnell Square. It was reconstituted again in 1939 as Cumann Camogaiochta na nGael. For a period in the 1930s it organised women’s athletics events. A breakaway Cualacht Luithchleas na mBan Gaedheal continued in existence during 1939-51 as clubs in Cork, Dublin, Kildare, Meath and Wicklow disaffiliated in a series of disputes, largely over whether male officials should be allowed to hold office and whether players of ladies' Hockey should be allowed play camogie. The last of these disputes was not resolved until 1951. The decision to change the playing rules from 12-a-side to 15-a-side teams and to use the larger GAA-style field led to an increase of affiliations after 1999 from 400 clubs to 540 a decade later.

A new constitution in 2010 shortened the name to An Cumann Camogaiochta and accepted the English title Camogie Association on official documents for the first time, reflecting the increased presence of the game in Europe, North America, Asia and Australasia.

Lógó na Camógaíochta