SIMILAR IMAGES

IMAGE INFORMATION

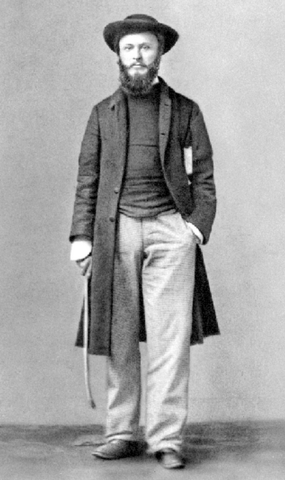

EditJohn Sheepshanks - Born February 23, 1834 in London, England - Died June 3, 1912 - Burial at Norwich Cathedral

Sheepshanks was educated at Christ's College, Cambridge. Ordained in 1857, he was a Curate at Leeds Parish Church and later the first Rector of New Westminster and Chaplain to George Hills, the Bishop of Columbia.

The First Rector of Holy Trinity, 1859-1866. He arrived in New Westminster in August 1859. Sheepshanks borrowed 1,000 pounds from friends in England, held a land-clearing bee, and laid the foundation for Holy Trinity Church in 1860. This church eventually burned in 1865 while Sheepshanks was soliciting funds in England for the church. He returned to New Westminster in April 1866, with funds he had collected for the church totaling 1,200 pounds. While planning the new church he was forced to resign due to the failing health of his aging parents. On his way back to England he crossed Northern China, 700 miles of Gobi Desert, through Siberian wilderness, over the Ural Mountains, and to Moscow. He traveled on foot and unarmed, and returned to England in 1867. In 1868 he became Vicar of Bolton, Yorkshire. In 1870 he married Miss Margaret Ryott. They had 13 children. In 1873 he was made Vicar of St. Mary's Anfield, Walton-on-the-Hill, Liverpool. During his time in Anfield, he petitioned for a school to be built for boys in the local area. St. Margaret's School was born. In June 1893 he was consecrated Bishop of Norwich. He resigned from the post on the February 19, 1910 and died on June 3, 1912 at 78.

Sheepshanks was also a noted author,

The Sheepshank connection to Hockey:

On January 9, 1862 the Fraser River froze over from Lulu Island to Hope. You could walk from one side of the river to the other. In fact, the first reference to Hockey being played in British Columbia notes the game was played on the frozen surface of the Fraser during this brutal cold snap. “Hockey sticks were fashioned from cedar,” writes John Cherrington in The Fraser Valley: A History, “and the male portion of the population—bureaucrats, parsons, storekeepers, woodsmen and Indians alike were all engaged in this exciting game upon the broad river.” The local native people said it was the coldest winter in their history.

In his memoirs, the Reverend John Sheepshanks wrote about this period of January, 1862:

" A wonderful sight it is to see the huge fields of ice

being hurried along by the rapid current, grating against

the fringe of strong ice which clings to the shore until they

have cut it, and it has cut them as straight and as evenly as

a glazier cuts an irregular piece of glass with his diamond —

and to see them when brought to a jam crunched against a

projecting piece of land, and smashing up and still borne on

by the current, forming quite a mound of ice fragments — and

to see them overlapping each other, and forced on to each

other's backs, and slipping about until broken, or welded

together by the frost. All this is striking, and the sound

perhaps still more so. It is grand and solemn to hear

morning, noon, and night that continual crashing going on."

The frost brought with it opportunities which no

Englishman can resist. For the first time since the Creation

skating began on the hardened surface of the river. Early

one morning the young Siwash rushed into Mr. Sheepshanks'

room to tell him, in much excitement, that a Boston man

(that is, American) was moving about in a very quick and

surprising way upon the ice.

" It being then apparent that we were in for a spell of wintiy weather, various preparations were made,

notably by the Canadian portion of the population for winter amuse-

ments. Sleighs were rapidly made, and presently the ladies

were being driven about in the rough equipages, made smart

with skins, and jingling with bells. Hockey sticks were

cut from the forest, and the male portion of the population,

officials, parsons, storekeepers, woodmen, and Indians, were

engaged in this exciting game upon the broad river. This

has continued now for some weeks. Occasionally carts

come down the river upon the ice, and cattle are driven

across to the other side. Business is at a standstill, and

sleigh-driving and hockey have been the order of the day." ,

Communication with the outer world ceased. This sent

up the price of provisions, but had an effect even harder to

bear, since it stopped all news from England at the time

when the Northern and Southern States of America were at

death grips, and the Mason and Slidell incident made the

peace of Great Britain itself tremble in the balance.

Accustomed though they were to rough it, the winter of

1862 brought with it more demands upon the patience and

endurance of the settlers of New Westminster.

" When I awake in the morning the bucket of water for

my bath is frozen solid. The first thing to be done is to

light a fire — taking care not to touch a piece of iron or

steel — put a lump of ice into a saucepan, and so get some

water, then pour that, when hot, upon the bucket of ice, and

so we can wash.

*' My blind fell down the other morning, and I fastened

it up again by driving a nail in with my sponge. I cannot

easily comb my hair, for it is frozen together. My upper-

most blanket is hoary with my frozen breath : I make a

snowball of the hoar-frost and throw it at Knipe.

" All the bed-clothes near my mouth are stiff with ice.

When one proceeds to breakfast, the cups and saucers are

stuck hard to the cupboard. The bread is frozen, and must

be put in the oven before it can be eaten. The ink is solid

and in the evening the camphine wiU not bum. But, not-

withstanding, I like the weather. The cold affects one

more in England because of the damp and wind. Here, in

the heavy frost, there is no wind. Indeed, if there were, we

could not live."

For no less than four months the great river remained

fast bound in ice. Milder weather brought with it water

and slush on the surface, but the ice still remained, showing

how deeply the frost must have penetrated. No steamer

was able to come up from Burrard's Inlet: life with the

outer world still languished.