The NHL and the Hockey Hall of Fame have never heard of Barry Wilmont.

However, the Copenhagen man is telling an intriguing tale of how he played a major role in replicating the Stanley Cup in 1963, helping to unravel some of the mysterious history involving one of Canada's most venerable symbols.

Wilmont, a Canadian-born artist who has lived in the Danish capital for most of his life, was initially sworn to secrecy when he was asked to engrave the replica in 1963, but doesn't really know why he was told to keep it to himself.

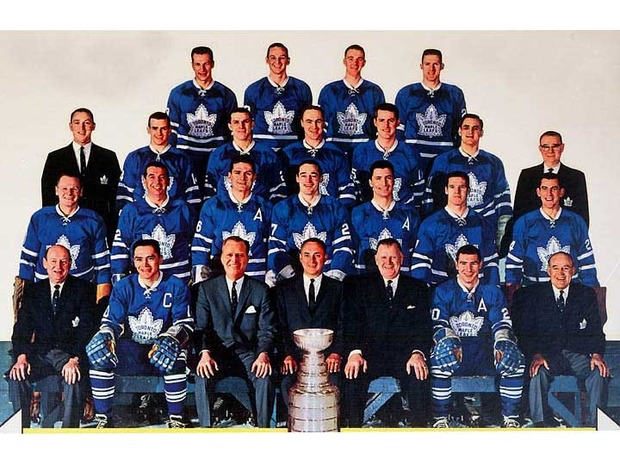

According to a history of the Cup by Mitchell Szczepanczyk, only a few NHL officials and the Montreal silversmith who created the trophy, Carl Petersen, knew about the replica, first raised in victory by the Toronto Maple Leafs in 1964. The secret, which lasted about three years, suggested the NHL might have been sensitive in letting the public know it was using a replica at playoff time.

The secret, which lasted about three years, suggested the NHL might have been sensitive in letting the public know it was using a replica at playoff time.

The new trophy was the first of several different versions of the Stanley Cup presented to the NHL champions every spring that didn't feature the original bowl donated in 1892 by Canada's then-governor general, Lord Stanley. The bowl was the original Stanley Cup and gave the evolving trophy validity because it remained the integral part.

Suddenly, though, the original bowl was gone and replicated on an entirely new trophy, a fact that might still surprise many fans as the NHL continues to mythologize the trophy, leading to a public perception that the Stanley Cup we see every spring is the real McCoy.

Say it ain't so, but it appears the last team to hoist what was the real Stanley Cup was the Maple Leafs, who won it in 1963, a year before they won the replica. The Leafs also won the real Cup in 1962.

Left to Right - Presentation Stanley Cup - Original Stanley Cup - Replica Stanley Cup

Wilmont thought the trophy he engraved was the backup, but that was not the case. He didn't seem to know that the one he copied from had long been dismantled and its various pieces, including Lord Stanley's bowl, placed on exhibit at the Hockey Hall of Fame in Toronto. He was also surprised to hear that the replica he engraved already had a significant history of its own, being presented to 42 Stanley Cup-champion teams and having visited the Oval Office in the White House on many occasions.

A second duplicate was made for the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1993 by Louise St. Jacques, owner of Boffey Inc., a Montreal silversmith that has been the official engraver of the Cup since 1979.

The Hockey Hall of Fame admits that documentation involving the history of the Cup during the earlier era is poor and that it has no record of Wilmont being the engraver. It does know that Petersen, who was born and raised in Denmark, was the official engraver of the Cup from 1948 to 1979. (Petersen died in 1977.) In 1962, he was given the task of replicating the entire trophy.

NHL president Clarence Campbell had decided parts of the trophy were too thin and fragile, particularly the historic bowl. Lord Stanley purchased the bowl for the equivalent of $50 after he decided a championship trophy was needed for Canadian amateur hockey. It was first known as the Dominion Hockey Challenge Cup.

To add to the NHL's worries, a Montreal man had attempted to steal the trophy during the 1962 playoffs from old Chicago Stadium, home of Bobby Hull and the Blackhawks, then the defending Stanley Cup champions. Ken Kilander told police he wanted to take the trophy back to Montreal, "where it belongs."

Wilmont, who was contacted by the Citizen on the advice of a reader, was born in 1936 in Winnipeg and was taken to Denmark in 1940 to live with his grandmother's family. He returned to Canada in late 1962 or early 1963 with his wife, Liz, and his daughter, the first of their three children. He said his engraving skills helped him land work at the Henry Birks jewelry store soon after the family arrived in Montreal.

Petersen, who apparently heard through the grapevine that a master engraver from his homeland had recently arrived in Montreal and was working at Birks, came knocking in the spring of 1963 and invited him to his Mackay Street workshop.

"When I arrived, he took me into this room where there were two Stanley cups," the 70-year-old Wilmont recounted from Copenhagen this week. When Petersen explained in Danish what needed to be done, Wilmont was overtaken by a strange sense that he was flirting with trouble, suspecting Petersen was a thief. He had heard about the incident in Chicago the previous spring, but thought the Cup had actually been stolen.

"Please, please," Wilmont recalled telling Petersen in their mother tongue. "I don't want anything to do with this. I've heard about what happened in Chicago. Someone stole the Stanley Cup."

Petersen calmed Wilmont and explained that he had created a second Cup at the request of the NHL and now needed an engraver to painstakingly copy the many names and dates from the old trophy onto the new one. He was also to do the same with every nick and scratch on the old trophy.

Wilmont said he had no idea why Petersen, then 68, didn't use staff from his own company to do the work, but added that the silversmith made it clear he wanted him to engrave the new trophy. Perhaps it was because the work involved duplicating old engravings, a task with which Wilmont had expertise.

Wilmont said he was told to keep quiet about the project, and he was given six months to complete the work.

"Mr. Petersen said I shouldn't speak to anyone (about the assignment) for about 10 years," Wilmont said. "He said: 'Don't spread the word that you have the Stanley Cups (at home).' "

If someone knocked on his apartment door, he was to hide the trophies or cover them with blankets, Peterson said, according to Wilmont.

Wilmont says he seems to remember taking the two trophies, wrapped in blankets, by car to his apartment on Hingston Avenue, near Sherbrooke Street in Notre-Dame-de-Grace, but he can't remember whether it was Petersen or a cabbie who drove him home.

He quit Birks when he took the job, but he continued to take other contract work while he engraved the new Cup.

What was of tantamount importance was that the engraving had to be a precise copy of what was on the old Cup, Wilmont said. With cushions under the trophies to protect them and his dining-room table, Wilmont copied date after date, name after name. He used strips of special paper and a variety of powders and liquids to get a print from the old Cup before transferring the impressions left on paper to the new trophy. Then he engraved the impression on the new trophy using etching instruments. He repeated the process over and over before turning his attention to copying the nicks and scratches.

"I had to be very, very careful," Wilmont said, recalling that some of the engraving on the old trophy had been badly done while other work was "very beautiful."

With the trophies perched on his table, he said getting impressions from the old bowl proved to be awkward. He called Petersen to see if the bowl could be removed.

"Just twist it off like a lid of a jar," Petersen told him. When he removed the old bowl, he noticed how thin the silver from which it was made from had become. "The bowl felt like glass," he said.

He remembers the name Montreal AAA, which he engraved into the new bowl after getting an impression from the original. That Montreal team was the first club to win the trophy, in 1893.

Wilmont said he finished the job in about four months, and delivered the two trophies to Petersen on an unbearably hot day, so he thinks it must have still been summer, well before the start of 1963-64 NHL season. He said he received about $900 for the work.

What the Hockey Hall of Fame did with the old trophy is unclear. In fact, some accounts have no mention of a replica being made in 1963. Some say the three rings or bands that formed the neck of the trophy were replaced in 1963 and sent to the Hockey Hall of Fame, where bands of earlier Stanley Cup trophies were also kept. Some say the old bowl was officially retired in 1969, and another says 1970.

It's not clear what happened at that time to the rings or bands that formed the barrel or bottom part of the trophy. Some reports seem to imply that most of the old bands are still part of the trophy that is presented to the winner at the end of the playoffs.

Wilmont said he was under the impression that the old Cup was stored in a vault in an Ottawa bank for many years.

Louise St. Jacques, who took over Boffey's Silversmiths, the Montreal company that became the official engraver of the Cup after Petersen Silversmiths closed in 1979, said the old Cup was taken out of circulation in 1963 after Petersen delivered the new one. Petersen's name is stamped on the bottom of the black base of the trophy presented to the Stanley Cup champions, according to Hall of Fame curator Phil Pritchard.

What was different about the replica was that, unlike the old one, the bands or rings on the trophy's barrel, first introduced in 1948 and then revamped in 1958, were detachable, allowing blank replacement bands to be used when there wouldn't be any room left on the Cup to inscribe the names of championship teams and their players. The first replacement band went on the Cup in 1991, and a second replacement band will be installed on the Cup this fall after the names of the 2005-06 champion Carolina Hurricanes players are inscribed on what is now the bottom band.

Over the years, winning teams have taken the Stanley Cup to the White House, where it was shown off to presidents George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush. Players and coaches from the winning team are each given the Cup for a day or two. The trophy has been taken to their hometowns, on fishing trips, steambaths, bedS, strip clubs, an auto glass factory in Hawkesbury, Moscow's Red Square, and mountaintops in B.C. and Colorado. Even though a staff member of the Hall of Fame accompanies the trophy wherever it goes now, it has been dropped, dented, and thrown into swimming pools. An older version of the Stanley Cup, featuring the original bowl, was used by former Ottawa Senators star King Clancy in 1927 as an ashtray for his cigars. In 1940, Lynn Patrick and other members of the New York Rangers used it as a urinal. A cow ate hay out of the replica when Larry Robinson, coach of the 1999-2000 Stanley Cup champion New Jersey Devils, brought the trophy to the Merrickville area.

After the Carolina Hurricanes won the Stanley Cup, a member of the maintenance crew at the RBC Center in Raleigh, North Carolina, dropped the trophy during celebrations in the team's dressing room. The edge of the bowl was slightly cracked. It was to go in for repairs. The team was told not to worry, that worse things had happened to the trophy.

Wilmont, who returned to live in Denmark in 1965 and has revisited Canada several times since, was a little hurt to hear the news about the abuse his trophy had endured.

"I don't understand why they would do that to it," said Wilmont, who graduated from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen and still makes his living as a painter and sculptor.

"I am proud of my Stanley Cup and Mr. Petersen's. I would treat it a little differently," he said. "I think in (Denmark), it would be treated with more respect.

"I feel a little bit sorry ... (The Stanley Cup) is like a bit of royalty, isn't it?

Article originally published by Hugh Adami at Ottawa Citizen / Canwest - 2006